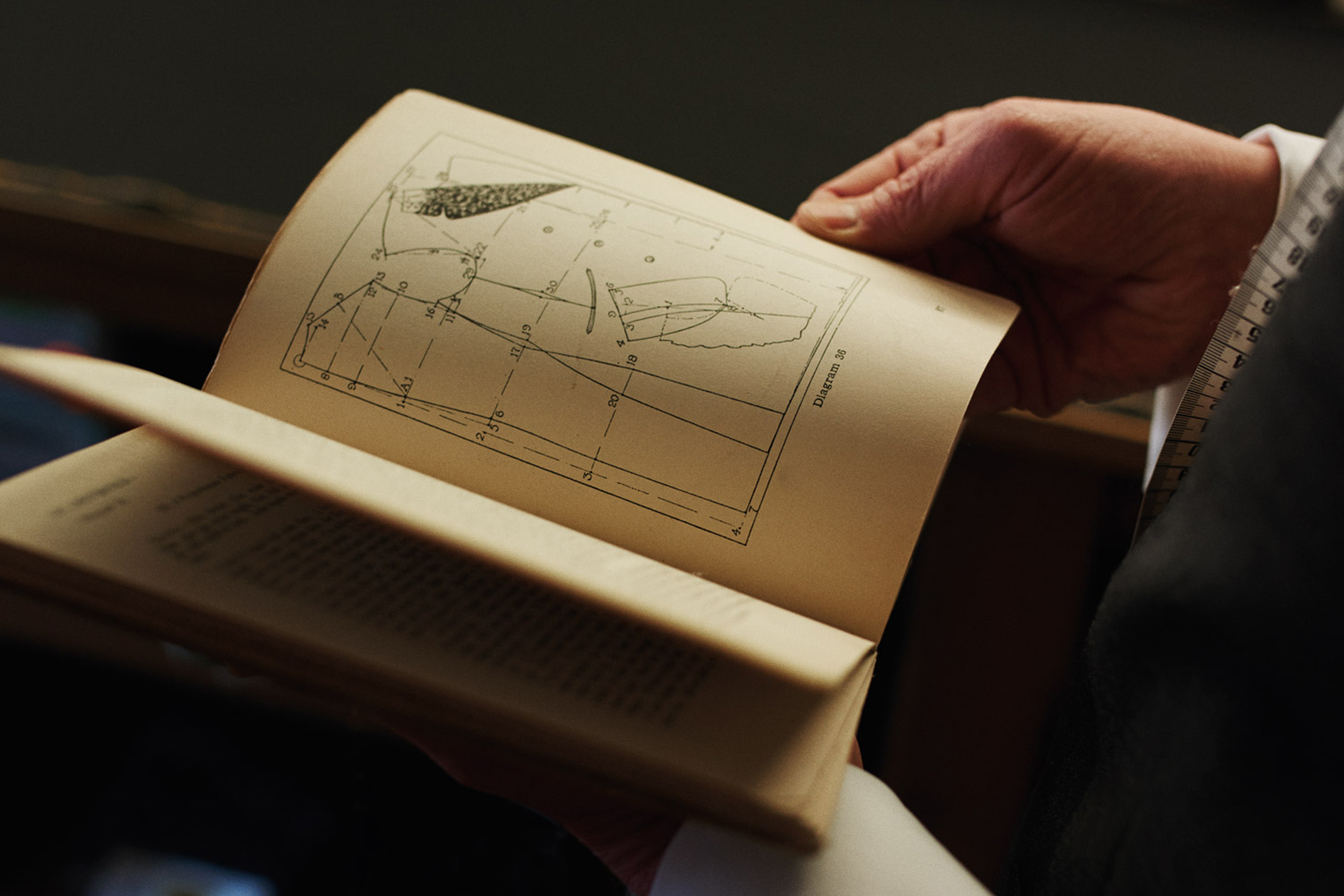

In the hills and fields surrounding the Cumbrian market town of Brampton, Mother Nature is showing her Autumn Winter swatches. It’s not the kind of place where you’d expect to stumble upon a Savile Row-trained bespoke tailor housed in a workshop just off the main square, tape measure slung around his neck, quietly performing the part-science, part-alchemy that transubstantiates bald measurements into geometric shapes on cloth — but then English Cut founder Tom Mahon came into the business, in his own words, “by accident”.

“I grew up here,” explains Mahon, whose previous studio in nearby Warwick Hall — a 30s country pile on the banks of the River Eden — overlooked his old primary school. Mahon’s education in tailoring started when his formal one finished: like with most young men of a certain age his ambitions were modest. “In the grand scheme of things, it’s all about girls and alcohol when you’re 18 years of age, isn’t it?” the now husband and father of three young children admits with a wry smile. To earn some “beer money” before college Mahon took a sixweek summer job at a storied local tailor called S. Redmayne, which turned into a much longer stint than he could have anticipated: “It came time to leave and Michael, the owner and still a good friend of mine, said, ‘We think you have a vocation for it. If you stay, we’ll make you a suit and we’ll send you to college.’ ‘Done.’ That was 31 years ago.” After 12 months as an apprentice with S. Redmayne, Mahon was duly sent to Darlington college (now renamed Teeside university) in the north east to learn industrial pattern cutting and grading — the aforementioned part-science, part-alchemy — and went on to work with the local firm for a total of seven years. But that doesn’t explain how he wound up plying his newfound trade at Anderson & Sheppard, arguably the most prestigious of all Savile Row tailoring houses. “The interest in girls and alcohol never changed,” he laughs. “When I was 25, I had a girlfriend who was going to university in London. I thought I should really move there, too.” This being before the advent of LinkedIn and similar networking sites, he wrote letters to Savile Row firms. “Everybody offered me a job, which astonished me,” he says. “The response made me feel quite special, but looking back, I was only special in one regard: there were no young tailors around. I was unusual in that I’d done a good apprenticeship with a respected company.” One suspects he is being unusually modest, but either way he found himself in demand: “I picked Anderson & Sheppard because I preferred everything about them.”

Despite being the youngest cutter there, Mahon ended up making for the most prestigious Savile Row house’s most prestigious client, the Prince of Wales (once he’d been vetted by the security services, that is). “Which was nice,” Mahon says with characteristic deprecation, unconsciously evoking the Fast Show sketch. Framed in Mahon’s workshop is the tattered remains of one of HRH’s “coats” — Savile Row speak for suit jacket — which had to be remade after the Queen’s corgis exhibited a taste for fine tailoring. Mahon’s ascension to Savile Row tailoring royalty seemed assured: “I did see myself working there forever,” he says. After five years, however, two factors conspired to usurp that plan: “The company changed and maybe I didn’t see myself there anymore,” he says. “And then I become homesick for this area. I like how we can live here. It’s very sociable. It’s very relaxed. You can enjoy driving a car. You can enjoy the evenings. You can finish work and go out walking or sailing. It’s just a nice place to live.” Mahon’s colleagues wondered if perhaps he’d gone off the deep end. “Everybody thought I was insane,” he says. “Looking back, I really was insane, because there was no Internet to let the world know what I could offer in terms of bespoke tailoring.”

Mahon declined overtures from Gieves & Hawkes and before he left, Anderson’s asked him to help train the then head trouser cutter John Hitchcock, the future managing director and 20 years Mahon’s senior, who retired as head cutter in 2014. But while it seemed a long shot at first, Mahon’s distance from London became his Unique Selling Point. Not having to operate a fully-fledged workshop in Mayfair, as anyone who’s played Monopoly can comprehend, saved Mahon money that he could pass onto his customers, undercutting the big houses by 20-25%. Not tied down, he was able to travel to where his customers were, in other cities such as Paris, New York and Chicago, something he continues to do to this day. And while his quality of life improved,that of the output did not diminish. Whilst at Anderson & Sheppard Mahon had previously been in the habit of couriering jackets to his favourite coat maker in and around the London area, a practise he continued after moving. He also found a surfeit of local craftsmen in Cumbria, plus lured his now head coat maker and co-director, Paul ‘Griff’ Griffiths, from Anderson & Sheppard. To attract custom, they relied on recommendation and that quaint tradition of writing letters. “Word gets around, and we still operated on the Row,” says Mahon, whose travels included to and from a small office at No.20 and then No.12; English Cut now has modest premises on nearby St. George Street. “We went along and we did fine.”

“I never thought anybody was going to pay any attention. The next minute, The Sunday Times voted it into their Top 100 Blogs List. Woosh! It went through the roof”

Then in 2005, Mahon’s friend Hugh MacLeod, a former advertising copywriter turned cartoonist and co-founder of internet-savvy consultancy Gaping Void, suggested that they draw on this newfangled information superhighway to give prospective clients more insight into the esoteric, opaque world of bespoke. Put simply, MacLeod spotted a gap for a tailor who could cut through the mystification and mythologising, instead talking shop to would-be buyers in an open and accessible manner. “He said, ‘I see what you do, and what you do is magic,’” recalls Mahon. “‘But your web presence is rubbish, and so are all the other tailor’s sites’, because all they say is: here we are, we make the best suits in the world and they cost a lot of money. Why don’t you explain to people what actually happens and what they get, just like you do to me in the pub?’” Proposing that they start “this thing called a blog,” without further ado MacLeod grabbed Mahon’s now vintage camera phone: “He took a photograph of some clothes on a rail and said, ‘There you go: there’s your first post.’”

The Rack, as it was called, unexpectedly became the subject of much focus. “I enjoyed writing and telling a story,” says Mahon. “I never thought anybody was going to pay any attention. The next minute, The Sunday Times voted it into their ‘Top 100 Blogs’ list. Woosh! It went through the roof.” Within six months his sales had tripled, with everyone from clients wanting to buy suits to students wanting to intern with him beating down his virtual door. The main driver for the traffic was that “everybody loved the transparency of it all”. Mahon was frank and forthright, not only about his own process but also the rest of the tight-knit and traditionally tight-lipped industry, which was particularly welcome to those looking to smartly invest several thousand pounds in a suit. “I kept getting asked what I thought of everybody else in the business,” says Mahon. “It would almost always end up at the level of, ‘Look, I drink with him in the pub on a Thursday night and he’s one of the best cutters I know. If you want to try him out, take it on my recommendation: he’s brilliant, he’s taught me loads.’” By making the codes of his traditional craft “open source”, Mahon became an unlikely internet entrepreneur, at least within the domain of bespoke: “Now they all have blogs but we did it first.”

The Internet is central to the next iteration of Mahon’s business — English Cut 2.0, if you will — as is a desire to pass on his knowledge to the next generation of both tailors and clients. “There’s a realisation that comes to everybody that you’re getting older, especially in my type of business,” says Mahon, who as a master tailor is one of a dwindling number of keepers of the sacred sartorial wisdom. “The reality is that if anything happens to me, the business ends.” With that in mind, English Cut is expanding into the more attainable made-to-measure service and ready-to-wear, including an innovative online made-to-measure offering — but, crucially, without erasing the history of quality and attention to detail that has fuelled the brand so far. “We have to keep on the same track as we’ve always done,” says Mahon. “We couldn’t just go to a manufacturer, sew our labels in the product and that’s it. So we set about it in a totally different way.”

As always, Mahon didn’t want to follow the herd when it came to expanding his business. “I know there are nice things that get made in China but I just didn’t want to go where everybody else was going,” he says. Instead, Mahon jumped on a plane to Japan, world-renowned, not just in menswear, for its manufacturing skills and attention to detail. With the help of his contacts (he won’t disclose any names but hints that it involves the owner of a major Japanese high street retailer) Mahon began a three-year journey to find a manufacturer who not only met his exacting standards but would be willing to adapt to his singular way of doing things. Even given the inherent respect of the Japanese for the institution of Savile Row — their very word for suit, sabiro, is a corruption of the name — it was a tough ask for a factory to accept the cost involved in changing an existing set-up, not to mention the risk. “We made them do things they were convinced would not work,” says Mahon. “They were like, ‘those armholes will be too small, the suppression through the waist is too much…’ But we pulled it off to the relief of everyone involved.”

Together with his trusty head coat maker ‘Griff’, Mahon reconfigured all the patterns to preserve as many of the qualities of English Cut as possible. That extends from the drape of the fully canvassed chest, which moulds to your body better than a “fused” or glued jacket — “there’s even a proper flower loop behind the lapel” — to the stiffer, wider waistbands: “Ready-to-wear trousers have these flimsy tops — they’re just awful.” Whereas what usually passes for ‘made-to-measure’ often amounts to little more than ready-to-wear with the trousers taken up, the uppermost of English Cut’s three tiers in particular is much closer to the level of bespoke. “You’d have to look very closely to know that it’s not, especially as it’s hand-finished in England,” says Mahon. Although not given to self-aggrandisement, he maintains that the end product withstands comparison to anything else in this market. “I’ve seen top brands with heritage but their garments just look the same as everybody else’s, and I know for a fact that it didn’t take them three years to develop it,” he says. “They went out there, they got offers, they made a few changes, had lunch and went home. Whereas we ended up dragging ourselves out there as many times as it took to get it right.”

The made-to-measure ordering process is another area where Mahon is making significant alterations. While English Cut is by no means the first company to offer online customisation, it’s perhaps the only one with a Savile Row-trained master tailor underpinning it. But how do you encode that alchemy onto a computer. “There are certain measurements that fundamentally guide what others should be,” says Mahon. “We worked out an algorithm that when one number is this, the corresponding number should be that. And it worked really well.” The English Cut suit engine will also be ingeniously designed to generate tasteful results. “One of the first questions that should be asked when you come to a tailor is what you want the suit for,” says Mahon. “People come in all the time and say something like, ‘I want a blue chalk stripe suit.’ ‘May I ask what you need it for, Sir?’ ‘My sister’s wedding.’ ‘Ah OK, are you really sure you want a blue chalk stripe? Of course, if you really want such a suit, it’s yours. But if we don’t guide and clarify choices for you we’re doing us all a disservice in the worst possible way — it’s not about sales but about trust’”. Instead, depending on the stated intention, a selection of suitable cloths will be offered, along with descriptions of their characteristics and what else they can be worn for, followed by cuts and styles, which will be influenced by the customer’s shape and size: “And then we’re going to end up with a garment that will suit them and their needs.”

For those that prefer a more analogue tailoring experience, English Cut will have stores in London, New York and Boston, housing made-to-measure cloths, ready-to-wear clothes and staff who aren’t incentivised to sell you something ill-fitting. “I’ve met very sincere salesmen but they’re all sincerely wrong,” says Mahon. “There’s nothing personal about them, they’re just trying to earn their commission, but they’re not educated. We want to make sure that people are informed: our staff, our customers.” Whether online or bricks and mortar, the aim is for English Cut to be more accessible and less intimidating than going into a shop that looks like a gentleman’s club with a raft of royal warrants along the wall — especially for a generation that don’t know the difference between a notch and a peak lapel, let alone which one they want: “We want to take that worry out of it.”

As with his bespoke suits, Mahon is to create a business that will last, and get better with age — one that will also hopefully free him up to “spend all of my time teaching mini-mes”. Besides, you’re never too old to learn something new — a lesson he knows all too well. “Once, at Anderson’s, I cut two jackets for a former chairman of BSkyB in this multimillionaire cashmere,” he says. “I must have been in a hurry to get to the pub or something, because I cut them perfectly — but upside down. When you brushed the pile down, it went up. Six months later, I got summoned to the cutting room to find this customer with a jacket that was all furry like Chewbacca. I nearly died on the spot.”

Thankfully, the estimated £20,000 cost in today’s money didn’t come out of the young tailor’s wages, though he offered. Only the other day, the now master was imparting this crucial lesson to his apprentice. “I told him, ‘When you cut the suit, the ticket on the cloth should always be placed on the right,’” says Mahon. “But the cloth merchants change, like everyone else. So being cocky, I grabbed the cloth, spun it out, put the ticket to the right and was good to go, or so I thought. On this occasion the cloth merchant decided to ticket the cloth the opposite way. Who’s fault was that? Mine of course, for not checking everything, no matter how busy it was.” Thankfully, he knows now to double-check everything: “As the saying goes: ‘Think twice, cut once.’”